On May 18th, 100 or so top-ranking representatives from the golf industry went to Washington to tell Congress just how big an impact golf and the business of golf have on the USA.

In dozens of meetings with Senators and Representatives in the Rayburn Office Building on Independence Avenue, these key industry personnel hoped to make legislators aware of golf’s importance, and to ensure elected officials give due consideration to the golf industry, and the two million people it employs, when voting on environmental and labor regulations.

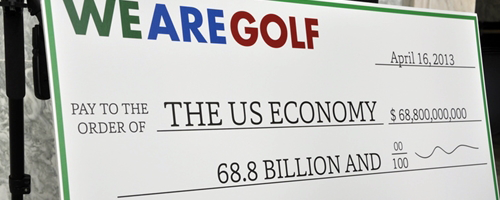

In a corridor leading into the area that served as the nucleus for the ninth annual National Golf Day was a giant faux check, made out to the US Economy and signed by the golf industry in the amount of $68.8billion.

That’s billion…with a B.

It’s a staggering amount – still some way off the $4.2trillion or thereabouts in sales the Consumer Discretionary sector records each year, but about double what the US film industry and Hollywood contribute to the nation’s coffers. Golf also makes over $4billion in charitable contributions every year, more than the NFL, MLB, NBA, and NHL combined.

Steve Mona, CEO of the World Golf Foundation which partners with nearly 30 organizations around the world to develop and support initiatives aimed at growing the game, marshalled golf’s troops on Capitol Hill for an umbrella organization called We Are Golf – a coalition of leading groups including the Club Managers Association of America (CMAA), Golf Course Superintendents Association of America (GCSAA), National Golf Course Owners Association (NCGOA), PGA TOUR, The PGA of America, the U.S Golf Manufacturers Council (USGMC) and the World Golf Foundation (WGF). It was his job to ensure Congress got the message, loud and clear.

“We think Congress sometimes has the wrong impression of golf,” he said. “I believe many Congressmen still think it is a game for the 1%ers, but that’s just not the case anymore. The average green fee in the US is $37, and 76% of golf courses are open to the public. We just want golf facilities to be treated like any other business, be it a bowling alley or barber shop. Golf courses and professional shops are essentially 15,000 small businesses, and there are thousands of other businesses involved with equipment, apparel, technology and so on.”

We Are Golf first descended on the Capitol in 2008 when golf, just like every other industry besides discount retail, home renovation, funeral services, and creature comforts (wine, chocolate, tobacco, lottery tickets, etc) was suffering in the midst of what came to be known as the Great Recession.

The number of participants plummeted as fewer people had surplus cash to spend on golf, so the revenue generated by golf courses, golf shops, in clubhouses and on golf web sites plummeted with it.

Then, as tech companies kept churning out fancy devices, and other sports and hobbies became attractive alternatives for young people, golf became less and less appealing to a large section of society which maintained it took too long to play, was inherently difficult, and cost too much. Given that the average round took so long, the average score for 18 holes was over 100, and that a new driver and set of irons might typically cost $1,500, the naysayers had a point.

Another factor in golf’s malaise was the disappearance of Tiger Woods from TV screens as his golf game deserted him following domestic troubles and various injuries. At the height of his powers in the early 2000s, countless people, old but primarily young, had been tempted onto the links. But they exited when the Tiger effect wore off and they discovered they’d rather go to the playground with the kids for an hour or two than play bad golf for five.

Statistics can lie but they can paint a pretty bleak picture too. The National Golf Federation (NGF) found that between 2003 and 2014 the number of people playing the game had dropped from 30.6 million to 24.7 million. Perhaps even more troubling was that the number of people between the ages of 18 and 25 playing golf had dropped by a third in the same timeframe.

Headline writers and other assorted sensationalists cried golf was dead. A June 2015 article in Men’s Journal began with a picture of an overgrown field in which you could see a tattered flag, an abandoned cart, and a headstone with the words ‘The Death of Golf’ written at the top. The image was clearly staged, but the point was made.

In the story itself, writer Karl Taro Greenfeld explained how surprised he was to hear his 15-year- old daughter tell him she was trying out for her school’s golf team. The girl apparently had little athletic ability, and Greenfeld was concerned she would be disappointed at being beaten by a bunch of what he called country club regulars.

But she did make it. Curious, Greenfeld asked the coach, James Palerno, how she had managed to make the cut. “There just isn’t the interest we used to have 14, 15 years ago,” Palerno told him. “Now I have kids showing up who have never hit a golf ball before. Kids are just less aware of golf. They have too many other options. And then when they find out it takes five and a half hours to play 18 holes, they’re just not interested.”

Davis Love, this year’s Ryder Cup captain and a We Are Golf supporter, alluded to the problem in Washington last week. “We’re all so hooked into technology that if we don’t bring it into the game, kids are going to get bored, and they won’t get excited about it,” he said. “We’ve got to modernize or it’ll get boring to the next generation.” Steve Mona agreed, adding “Millennials are the future of the game. We desperately need to bring in the younger generation.”

To do it, the golf that people of my generation (I’m 44) and older are used to is going to have to change. Stuffy country clubs with rich, white, male memberships, excessive water consumption and chemical usage by course superintendents, poor customer service at the cash till, polo shirts and khakis, old-fashioned yardage books, and all the rest of it have to go. Of course there will always be places for old-school types to play their stodgy game, but the standard golf fare will need to evolve quickly.

Those that follow the game know the changes are already taking place and have been for many years, in fact. Equipment companies have been employing former NASA scientists and absurdly-well qualified engineers to make space-age gear for a decade or more. Their products make the game easier and significantly more fun for less able golfers. Courses, and professional tournaments the public attend, are beginning to allow the use of cell phones, and courses are doing better at engaging their customers through the use of social media. Agronomists are developing turf that requires far less water to thrive and which can even survive on salt water. Rhett Evans, CEO of the GCSAA, told Congress there has been a 22% reduction in water-use on golf courses over the last eight years, and that golf course superintendents are using 33% more recycled water than they were in 2005. “The environmental benefits of golf courses are tremendous,” Evans says. “They provide over two million acres of green space, shelter and habitat for wildlife, and are the filter that take pollutants out of storm water which would otherwise travel downstream and into what we drink.”

And measures are constantly being taken now to reduce the amount of time it takes to complete a round. The USGA and R&A conduct numerous surveys and tests aimed at discovering ways to eliminate slow play. Developers are wising up to the fact golf needs something other than full-length, 18-hole courses, and existing facilities now offer shorter loops and junior tees.

Former LPGA star Nancy Lopez was in DC last week trying to get more recognition for ladies’ golf, and to throw her support behind We Are Golf. “Everybody still thinks they have to play 18 holes,” she said. “In the afternoon when you’re off work, just go putt, or chip, or play three holes. And why not just play nine? Give people another way to learn the game. Charge customers according to how many holes they play or how long they play for, not just an 18-hole round.”

This is similar to something I’ve mentioned to a couple of public courses in my hometown. Why not close the course for a few hours, one Monday morning every month, and charge new golfers $50 for a ten-minute clinic/lesson, an hour on the range, a sandwich and soda, and three holes of golf?

Mona addresses the time issue saying the game has to adapt to how millennials wish to consume it. “We need to offer golf in one-hour increments,” he says.

Mona also hopes the numerous participation programs on offer today – Get Golf Ready, The First Tee, PGA Junior League, USGA Girls Golf etc. along with hi-tech gear (laser/GPS rangefinders, interactive tournament scoreboards, swing analyzers, and so on) will boost the numbers playing golf.

The pro game will certainly play its part too. After the Tiger Woods era ground to a halt, no one it seemed could fill the void, but in the last couple of years a band of bright young things has emerged and is transforming the game we see on TV.

Steve Stricker, PGA Tour winner and one of Davis Love’s selections as a vice-captain for this year’s Ryder Cup, spoke in Washington about the young players currently making all the noise. “You have Jordan Spieth, Rickie Fowler, Jason Day, Rory McIlroy, and others changing how the game is perceived by the millennial generation,” he said. “They’re the beacons that are bringing people into the game as either fans or participants. They’re great players and great people.”

Something else that might help nudge the needle is the PHIT (Personal Health Investment Today) Act which will allow golfers to deduct virtually everything they spend on lessons, equipment, and green fees, from their tax bill.

According to the Physical Activity Participation Report, 81 million Americans are ‘inactive’ today compared with 70.4 million in 2007, a 15% increase. That inevitably leads to escalating healthcare costs. Indeed, the Employee Benefits Research Institute recently showed healthcare spending had risen from $2.6 trillion in 2010 to $3.2 trillion in 2015. It projected the figure would climb to $4.2 trillion in 2020.

With golfers burning upwards of 2,000 calories over 18 holes, you’d expect the government to do what it could to encourage people to play golf.

Olympic golf will also bring about changes, most noticeably in countries with less golf history than the US, but here as well. Kids, and adults, that watch the Games and see a golfer they may or may not have heard of be awarded a gold medal will surely become eager to at least go to a driving range.

And golf’s governing bodies will also need to contribute perhaps by altering some of the game’s notoriously complex and rigid rules, or by placing younger people in positions of power and responsibility. The USGA and R&A are in a tricky spot certainly. On the one hand they are guardians of a game over 600 years old which requires wise, thoughtful, and experienced leadership. But they also have to be flexible and wary of how the game is changing so rapidly. They need to uphold golf’s virtues and prestige, but also be able to move with the times and promote necessary change.

Whether it’s by modifying rules, fighting for an alteration to income tax legislation, building shorter courses, offering exciting new technology, providing new golfers plenty of opportunities to play, ensuring environmental safeguards, removing stringent dress codes, giving golfers different ways to pay for the game, or enabling ultra-talented youngsters to shine, golf is definitely making the changes it needs to make in order to thrive. The odds are probably against it ever reaching those heady participation numbers of 10 years ago, especially with entities like the Honourable Company of Edinburgh Golfers thrusting a spoke into the wheels of change by voting to keep women out of their club. But the vast majority of current golfers are on board with the changes. It remains to be seen though, how many outsiders will join them/us for the ride.

Follow Tony Dear on Twitter @tonyjdear

Many moons ago, Tony played on the Liverpool University golf team at Hoylake, and then became an apprentice professional in Sussex, England where he taught the game, regripped members’ clubs, and listened to golfers dissect every one of the 112 shots they had just taken. He loved it, but unfortunately had a few health issues which meant he had to write about the game instead. He’s a former golf correspondent of the New York Sun, and currently contributes to the R&A’s Open Championship magazine, Links, and a few others. He still plays golf occasionally, but is…how do you put it…very bad.

Back to #GolfChat Authors